Quarterly Update - 2025 Q4:

Hands gripping the steering wheel, I steer the car through the intense rain and gathering dusk up the on ramp leading to I-5 South. Peering through windshield wipers on their highest setting, I find and fit my way into the creeping mass of southbound vehicles. I’m pleased to have ducked out of the annual Climate Friendly Forestry Conference with enough time to begin the three hour drive home one hour ahead of darkness. With the forecast calling for rain falling at between one and two inches an hour, the normally straightforward drive is now full of uncertainties - both for me and for my home region: “How much rain will fall? Is it foolish to make the run for home, or would I be better off sitting it out in a rest stop, sleeping the night in the sleeping bag that I’d thrown into the car after checking the forecast? How resilient and harmed will our region be as the masses of water rushes from the sky, onto the land and on to the sea? Who and what will be harmed and spared? How bad will it get? What lies ahead?”

Thanks to six decades of life in the region, I am accustomed to these types of early winter heavy rainfall events; they are familiar and will pass - just as they always have. But having lived through events in the past five years, a new uncertainty has been added to the mix. Back in June of 2021, when we watched a round of hot weather settle over our region, raising the temperature well past the 100 degree mark, we thought to ourselves “this is normal..”. But when the temperature peaked at a sizzling and damaging 116*, it became clear that “this is not normal; what we’ve counted on in the past may no longer be counted on.”.

Meanwhile back on an awash I-5, I peered into the blur of red tail lights ahead. More of the road’s surface was water than pavement, and wondered “is this just a normal soaking weather system - or might this be something different?”. The answer was unknowable, but it mattered. If this was normal then slogging on toward home would bring reasonable and manageable levels of risk. If this, like the spiking heat, was beyond normal, pushing for home could be a bad and dangerous choice. Now a new challenge has been added to the already long list of behaviors of a responsible citizen: finding the right balance between the increasingly common and bad habit of irresponsibly attributing too much to our role in changing the climate or under acknowledging our role. My feelings that we have crossed the line into new and uncharted territory are explored in more depth here.

Just as I my wondering about this excess of rain kept me company traveling down the dark road home on this December night, thoughts of wonder were stimulated in December of 2019 by the opposite - when the normal rains did not return. This abnormally low level of precipitation caused our forest-traversing creek not to rise so that the coho, whose annual return we count, were not there.

____________________________________________________

State of Wonder - in a Time of Wondering –

This weekend over 100 of us gathered in our Timber Forest for the annual ritual of welcoming the Coho salmon home from their long and hard circuit of the Pacific and their 1,000 foot, 100 mile climb back up the Nehalem River. It is uplifting to consider how those before us also watched and waited on the banks of this river for thousands of years. In our over thirty years of watching and waiting, the salmon have always miraculously arrived.

Several days after the event, I reflect on those who joined us and particularly those sharp-eyed fish welcomers in their teens. I consider what thoughts and feelings they might have had during the day. Did they wonder why their parents roused them from their perfectly good, deep and much needed sleep too early on a dark dreary morning to drive through pouring rain to stand in a chilly, muddy forest with a bunch of odd strangers? Did they wonder whether there’d be spawning salmon – and a warm bowl of chili, by a crackling fire, in the good company of people they’d just met while standing side by side on the creek bank scanning the pools for fish? I expect that they were unlikely to wonder since experience in past years had taught them that this was something that they could count on – something to look forward to – and worth getting out of bed for.

But this year there were no fish. Did our young companions spend much time wondering why? There is no doubt that they heard the adults around them move quickly from wondering mode to analysis mode. While they heard one person accurately explain the fishless creek with “there always have been and always will be dry Novembers and this low stream flow is just part of the natural cycle of things in this Coast Range...”, they also heard someone on the other side of the fire conclude “it is so sad to see yet another impact of the climate crisis and the unravelling of the ecosystems....”. Regardless of how much we wonder, we can and will never know which commentator is closest to the truth. I wonder about what our young folks made of these comments, and the elders’ quickness to make statements when questioning might be more appropriate. As they pulled on the cross cut saw, while digesting their chili and cookies, do they, like me, wonder about what lies ahead – for the Coho, for themselves, for all of us, and the forest? As they walk through the rain dripping forest and along the crystalline creek, do they join me in wondering how it all works and how it could ever be so beautiful and special?

I wonder, in this time of wondering.

_________________________________________________________

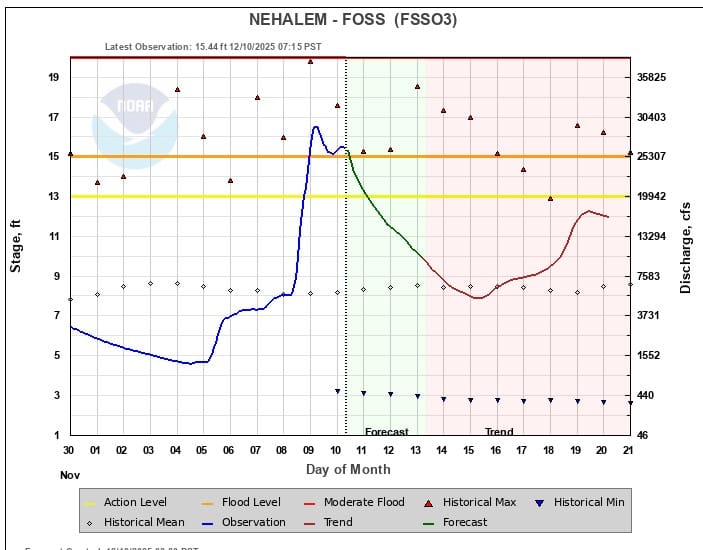

After safely surviving the the sodden drive home, I arose the following morning anxious to learn what light the sea of available data might shed on my wonderings of the previous night. How much rain did fall? How high were the rivers rising and might they rise? After seeing that one of our home rivers, the Nehalem, had risen above flood stage, I scanned through lessons to be learned from the hydrographs of other rivers across the region.

Though rivers were above flood stage all across the region, the Skagit stood out as the river most likely to cause serious damage. Having lived close to the Skagit’s final miles, I read with interest of how leaders in nearby Mount Vernon had invested in a removable wall designed to prevent the flooding river from inundating the town’s center. Over breakfast, I read that the Skagit was forecasted to crest several inches higher than the wall. What would happen?

Several hours later, the same hands that gripped the steering wheel through saturated Tacoma gripped the handles of a pick as I worked to redirect the water’s powerful flow from running down a road in our forest. In normal conditions, strategically placed water bars channel high water off of the roads and into roadside ditches. With rain still ponding down on my jacket’s hood, the futility of my effort rapidly became clear; rainfall from this storm had exceeded the capacity of this water bar. Redirection of the water off of the road until the flow of water down the road decreased enough to let us place a new, deeper water bar. Looking beyond the interactions between flowing water and our roads network, I was heartened to see that the wider forest appeared unchanged by these heavy rains that were causing such damage across the wider region. The relatively old and diverse forest with its lush understory functioned like a reliable and resilient sponge - absorbing the water and releasing it at a reasonable level to the clear running creeks. By daylight the following morning, the fate of Mount Vernon was clear. Thanks to fast action by the US Army Corp of Engineers, shutting off of the river’s flow through the upstream dams had helped to keep the Skagit from overtopping of the defensive wall. This time around, the human infrastructure had been resistant to the record high river flow.

Surrounding areas, along the Skagit and many other Northwest rivers were not so fortunate. As I write this on the first day of 2026, I wonder how resiliently these human and ecological communities will recover from the damage done by the floods.

The Wider World:

In previous versions of these quarterly updates I have struggled to share something of a summary of events in the wider world that have happened in the previous quarter. In hopes of making the task somewhat more manageable, I have filtered for those event which directly impact our work of caring for and restoring forests. For this update, I choose to delegate that task to a person better qualified than I am. In the post available here, historian Heather Cox Richardson shares her comprehensive summation of changes made by and to the US government in the past twelve months.

The forests that we care for are full of invigorating wonder, mysteries and uncertainties. As 2025 rolls into 2026, I reflect on what I’ve learned about how to simultaneously embrace both the wonders that have always been at the heart of our forests while also effectively wondering about what’s happening and what lies ahead of us.

What’s There to Love?

There is a good reason for ending these quarterly updates with a sampling from my overflowing bag labeled “what’s there to love in these forests?”. In this dark new year, I welcome this habitual shift of focus; perhaps you do too? This quarter I’ll focus on the welcome wonders of resilience, water and cycles.

Resilience – As shared above, as the intense, December storm cycle moved on to the east and we lamented the damage that it caused all across the region, I shifted my attention to checking on the status of our family’s three forests. How were they impacted by the strong winds and heavy rains? Driving the forests’ road networks, what was most notable to me was how minor the impacts of the multiple storms seemed to be. I discovered creeks running high and clear, but not flooding. Though I found cut out a number of road blocking trees, elsewhere, the forests remained upright and intact. Even though our family has spent decades working to build the traits of resilience to various stressors into the forests, one never knows how successful one’s been until the forests are put to the test. What I saw – and appreciated – on that post storm day, as the heavy flows of water made their ways downhill, was how resilient the forests have become. Stressed by high winds, the mix of species and ages of trees thrashed and bent, but didn’t break. Thanks to the diverse forest, with lush understories, plentiful downed logs and deep soils, the intense rains were caught and held instead of becoming dangerous and degrading rapid runoff.

Water Everywhere – A special moment from this cycle of storms sticks vividly with me. On the heels of the cacophony of loud winds and drumming rains came a calm silence. I was jolted into awareness of the abrupt change while I was busy planting and protecting young oaks in an open area halfway up the forest’s 1,000’ slope. Resting on my shovel, I took time to patiently listen. On this still morning, my ears were filled with the sounds of running water. From close by came the dripping of water from trees and the gentle chuckles of rivulets flowing down many small creases in the forest’s floor. In the mid distance I could hear the more insistent churning of a larger creek rushing on toward the nearby river. And above it all, in the far distance, I could hear sounds seldom heard on this hillside – the deeper rumble of the Tualatin River. From nearly a mile away I could see – and hear – its muddy, rushing floodwaters chewing away at bordering farmlands on its race toward the sea. Travelling on across the forest, I noted that it was impossible to find any place in the forest where the sound of running water could not be heard. Loren Eisley’s observation came to mind: “If there is magic on this planet, it is contained in water”.

Imbedded in Cycles - In each year’s cyclical seasonal round of emotions triggered by events in the forests, one rises above all of the rest – the moment of seeing the season’s first Coho salmon returning to the forest creek. My family and I thrill to crossing that line between anticipating their return and celebrating the first sighting. “They’re here!!”. So much makes it special, from our awe in the face of their far-travelling accomplishments to the spotting of bits of their spent bodies spread far across the forest reminding us of how they pump ocean-gathered energy throughout the forest’s web of life. This is a season with so many reminders of the cycles at the heart of all life. Ahead of the Coho’s return, we take a break from forest work when the welcome calls of southbound geese move us to look gratefully aloft. While the Coho, once again, school us in the interwoven realities of life and death, we celebrate that moment when daylight shift from growing shorter to longer. And finally, in this family that’s dependently connected to these forests, we celebrate the cycle of the shifting of leadership of the forest work from my generation into the willing and capable hands of the next and the prospect of welcoming newborn members in the coming months. A gift of this work is the impossibility of escaping such realities as our human, transitory insignificance in the wide, wild and wonderful world.

Atmospheric Co2 Measurements from Mauna Loa, Hawaii (link):

Dec. 2025 – 427.49 ppm

Dec. 2024 – 425.40 ppm